Note: FreeJupiter.com shares general info for curious minds 🌟 Please fact-check all claims—and always check health matters with a professional 💙

Aging has long been painted as a story of decline. Wrinkles appear, joints creak, memory gets patchy, and energy levels shrink. And when it comes to the brain, many people assume that time can only chip away at mental sharpness, leaving behind a steadily fading mind. But science has started to tell a different, and far more uplifting, story.

Recent research has revealed that parts of the human brain may actually become thicker and more robust as we age, rather than withering away. The finding not only challenges stereotypes about inevitable cognitive decline, but also paints a picture of the brain as a lifelong shape-shifter—one that continues adapting to whatever life throws at it.

The Brain’s Reputation: A Story of Loss

For decades, the popular narrative has been that the human brain peaks in youth and steadily deteriorates afterward. Imaging studies have shown that the cerebral cortex—the wrinkly, outer layer of the brain—tends to thin with age. This thinning has often been interpreted as a sign of lost brainpower, with less tissue assumed to mean fewer neurons and reduced mental ability.

It’s easy to see why this view stuck. Memory lapses, slower reaction times, and age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s reinforce the idea that brain decline is unavoidable. Yet, in recent years, research into neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize and rewire itself—has suggested that the brain is far more adaptable than once believed. And now, new evidence suggests that aging is not just about thinning and loss. It’s also about thickening and resilience.

Read more: Your Body Holds 7 Octillion Atoms—And Most Are Billions of Years Old

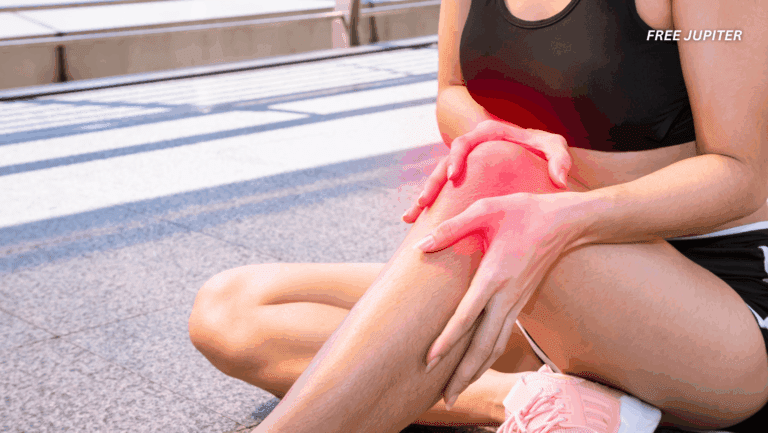

The Somatosensory Cortex: Your Touch Interpreter

The research in question zeroed in on a fascinating brain region known as the somatosensory cortex. This area is like your body’s interpreter for touch and physical sensation. Whenever you feel the texture of a sweater, notice the vibration of your phone, or sense the warmth of a coffee mug in your hand, this part of your brain lights up.

Far from being a simple surface, the somatosensory cortex is made up of several wafer-thin layers stacked on top of each other, each with its own function. Scientists often compare these layers to a stack of crepes or pancakes.

- The middle layer acts like a gate, receiving incoming touch signals.

- The upper layers fine-tune these signals, helping you distinguish subtle details—like whether your fingertips are brushing silk or denim.

- The lower layers work more quietly in the background, filtering out unnecessary information. Thanks to them, you don’t spend all day distracted by the constant pressure of your socks or the feel of your shirt collar.

Until now, researchers thought that all these layers thinned out together with age. But high-resolution MRI scans have revealed a different reality.

What the Study Found

A team of neuroscientists in Germany examined the brains of 61 adults between the ages of 21 and 80. Using advanced imaging, they looked closely at the structure of the somatosensory cortex.

- The lower layers did indeed shrink with age, fitting expectations.

- The middle and upper layers, however, were thicker in older adults than in younger ones.

In other words, some layers of the brain appeared to strengthen with age, not weaken. This was a striking discovery, as it showed that aging does not affect every part of the brain in the same way.

Why Some Layers Strengthen

So, what explains this unusual thickening? The researchers suggest that it comes down to one familiar phrase: use it or lose it.

The middle and upper layers are constantly active because our hands are always in contact with the world—grasping, typing, cooking, gardening, or turning pages of a book. These layers are bombarded with signals every day, so the brain invests in keeping them strong and efficient.

The lower layers, by contrast, handle subtler background filtering. Since their role is less demanding, especially in later life, they don’t get the same level of stimulation. Over time, they may thin out simply because they’re not needed as much.

But here’s the twist: even though these lower layers shrink, they don’t necessarily lose function. Researchers found that they increased their myelin content. Myelin acts like insulation around electrical wires, helping nerve signals travel more efficiently. This suggests that the brain is compensating for thinning by reinforcing the quality of the signals instead.

Read more: Doctor Says You Should Stop Peeling Off Those Banana Strings

Neuroplasticity: Not Just for the Young

These findings feed into the bigger concept of neuroplasticity. This is the brain’s built-in ability to adapt, reorganize, and forge new connections. Neuroplasticity has traditionally been viewed as a youthful advantage—something that fades after childhood. But studies like this are rewriting that story.

If certain brain layers are thickening with age in response to frequent use, then neuroplasticity is alive and well even in senior years. That means the brain is not a fragile glass sculpture but a flexible, ever-adapting system—more like clay than porcelain.

Everyday Examples of an Adapting Brain

If the science feels abstract, think about it in terms of everyday life. Consider how many older adults remain sharp by continuing to engage in mentally and physically stimulating activities:

- A 70-year-old who practices piano daily may strengthen brain regions tied to motor coordination and auditory processing.

- An 80-year-old gardener who works with soil, tools, and plants regularly stimulates touch pathways in the somatosensory cortex.

- Older adults who stay socially active or pick up new hobbies challenge their brains to adapt in new ways, reinforcing cognitive flexibility.

These activities keep the brain’s circuits engaged, which may explain why certain layers grow thicker instead of thinning away.

The Optimistic Side of Brain Aging

What makes this study particularly hopeful is its message: aging doesn’t automatically spell doom for mental ability. Instead, the brain seems to prioritize and protect the parts most used. This flips the narrative from one of inevitable decline to one of adaptability.

It also hints that lifestyle may play a powerful role. Just as exercise strengthens muscles, regular mental and sensory engagement may help the brain preserve and even enhance certain functions. In other words, knitting, woodworking, playing chess, or simply exploring new experiences could be more than hobbies—they might be brain training sessions.

Implications for the Future

While this study focused on a relatively small group and a single brain region, its implications are broad. If different layers of the brain age in unique ways, this opens the door for more targeted therapies in the fight against age-related decline and neurological diseases.

For instance, researchers could one day design stimulation therapies that deliberately engage and strengthen underused brain layers. Or they might develop training programs to encourage neuroplasticity in patients recovering from stroke or brain injury.

The key takeaway is that the brain has untapped resilience. Rather than thinking of aging as a one-way downhill slope, we can begin to view it as a complex reshaping process—losses in some areas balanced by growth in others.

A Brain That Never Stops Learning

Perhaps the most exciting part of this discovery is what it says about the human potential to keep learning. If the brain remains adaptable into old age, then there is no hard limit on acquiring new skills. An older adult can still learn a new language, pick up painting, or master digital tools, and in doing so, strengthen their neural layers.

The lesson here is simple: stimulation matters. The more we use our brains, the more they respond, sometimes by growing even stronger.

Read more: DNA Analysis of Beethoven’s Hair Show Toxic Levels Of Lead Present 200 Years Later

Final Thoughts

The image of the aging brain as a steadily crumbling organ is giving way to a more nuanced and hopeful view. Yes, some parts thin out over time. But others thicken, adapt, and compensate—proving that the brain is far from passive in the face of aging.

This research on the somatosensory cortex serves as a reminder that our brains are lifelong learners, constantly remodeling themselves in response to how we use them. Rather than simply “losing it,” we may actually be reinforcing and enriching key functions well into later years.

So the next time you pick up a new hobby, practice an instrument, or even just keep your hands busy with everyday tasks, remember: you’re not just passing time—you might be thickening your brain’s layers and keeping your mind stronger than you think.