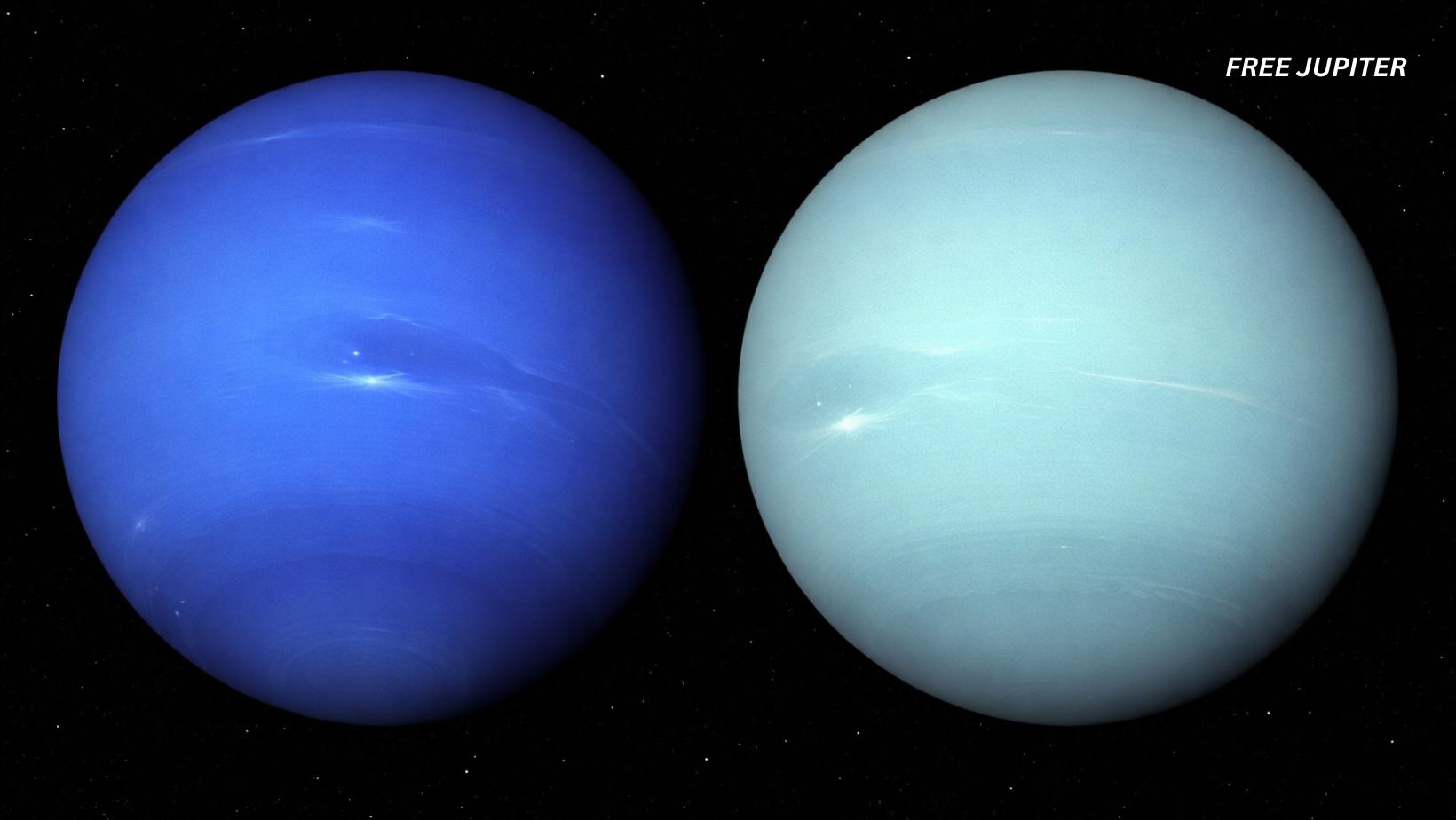

For decades, Uranus and Neptune have worn the same scientific label: ice giants. The name sounds dramatic, and it has stuck for a good reason. Compared to Jupiter and Saturn, these distant blue planets contain larger amounts of substances like water, methane, and ammonia. Under the crushing pressure deep inside the planets, those materials were thought to behave like solid “ices,” even though the planets themselves are not frozen in the everyday sense.

But a new study is gently poking holes in that tidy picture. According to recent research from scientists at the University of Zurich and Switzerland’s National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, Uranus and Neptune may not be as icy on the inside as we once believed. In fact, their interiors could be far more rocky—and far more dynamic—than the textbook definition suggests.

Why Uranus and Neptune Were Called Ice Giants in the First Place

To understand why this matters, it helps to know how planets are usually grouped. Scientists often sort the planets in our solar system based on what they are made of and how far they formed from the Sun.

Closest to the Sun are the rocky, terrestrial planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Farther out, beyond what astronomers call the “frost line,” conditions were cold enough for water and other volatile substances to freeze during planet formation. That region gave rise to the gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, and farther still, Uranus and Neptune.

While Jupiter and Saturn are dominated by hydrogen and helium, Uranus and Neptune were thought to contain much larger amounts of heavier materials—especially water and other compounds that act like ice under extreme pressure. This difference earned them their own category: ice giants.

Neat, simple, and easy to remember. Unfortunately, nature rarely stays neat and simple.

Read more: Scientists Say An Ancient Impact With Another Planet Could Have Sparked Life on Earth

A Fresh Look at Two Mysterious Worlds

Uranus and Neptune are among the least understood planets in the solar system. Only one spacecraft, Voyager 2, has ever visited them up close, flying past Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989. Since then, most of what scientists know has come from telescopes and computer models rather than direct measurements.

That lack of data has left plenty of room for assumptions.

In the new study, PhD student Luca Morf and planetary scientist Professor Ravit Helled decided to rethink those assumptions. Instead of starting with the idea that Uranus and Neptune must be ice-heavy worlds, they explored a much wider range of possible interior structures.

Their approach was unusual. Rather than building models around a fixed, water-rich interior, they generated many possible internal layouts with different density patterns. They then checked which of those models could realistically match what we observe, such as each planet’s gravitational field.

In other words, they let the data narrow down the options instead of forcing the planets to fit an old label.

More Rock, Less Ice?

The results were surprising. The models that best matched observations did not require Uranus and Neptune to be dominated by icy material. Instead, they worked just as well—or even better—when the planets’ cores were assumed to be largely rocky.

That does not mean there is no water inside Uranus and Neptune. Rather, it suggests that rock may play a much bigger role in their makeup than previously assumed.

Interestingly, this idea fits with what scientists have learned about other distant worlds. Observations from missions like New Horizons suggest that Pluto, for example, is made of roughly 70 percent rock and metal, with the remaining 30 percent being water ice. If a small, icy world like Pluto can be rock-heavy, it is not such a stretch to imagine that Uranus and Neptune might be similar on a grander scale.

Read more: Humanity Has Officially Found 6,000 Exoplanets, NASA Announces

A Planetary Interior That’s Not Sitting Still

Another intriguing finding from the study is that the interiors of Uranus and Neptune may not be calm and layered like a perfectly stacked cake. Instead, material inside these planets could be moving and circulating, a process known as convection.

On Earth, convection drives plate tectonics and helps power our magnetic field. Inside Uranus and Neptune, similar motion could help explain some of their strangest features—especially their magnetic fields.

Unlike Earth’s relatively tidy magnetic field, which has a clear north and south pole, the magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune are oddly shaped and offset. They are lopsided, complex, and difficult to explain using traditional models.

The new research suggests that layers of “ionic water”—water under extreme pressure that conducts electricity—could be generating magnetic fields deep inside the planets. These layers may sit at different depths in Uranus and Neptune, which could explain why their magnetic fields behave so differently.

According to the researchers, Uranus’s magnetic field may originate deeper inside the planet than Neptune’s, adding yet another layer to their differences.

Challenging a Comfortable Classification

One of the key takeaways from the study is that calling Uranus and Neptune “ice giants” may be an oversimplification. The label is not entirely wrong, but it may hide more than it reveals.

As Morf explained, earlier models often leaned too heavily on assumptions, while simpler, data-driven models lacked physical realism. By combining both approaches, the team aimed to create interior models that were flexible yet grounded in physics.

The result is a reminder that planetary categories are tools, not truths. They help scientists organize ideas, but they can also quietly limit how we think about unfamiliar worlds.

Read more: Scientists Find a Single Tree Can Capture Half a Metric Ton of CO₂ Annually, Cooling The Planet

What This Means for the Future

The researchers are careful to point out that their models still come with uncertainties. With so little direct data, it is impossible to say for sure whether Uranus and Neptune are more rocky or more icy at their cores. At the moment, both possibilities remain on the table.

What the study really highlights is how much we still have to learn.

Dedicated missions to Uranus and Neptune—long discussed but never launched—could finally provide the measurements needed to settle these questions. Better data on gravity, magnetic fields, and atmospheric composition would allow scientists to peel back the layers of these distant planets and see what they are truly made of.

Until then, Uranus and Neptune remain cosmic question marks. They may be ice giants, rock giants, or something in between. What is clear is that they are far more complex—and far more interesting—than a single label can capture.

In science, even the coldest, most distant worlds can still surprise us.

Featured image: GPT/5.1 Creation.

Friendly Note: FreeJupiter.com shares general information for curious minds. Please fact-check all claims and double-check health info with a qualified professional. 🌱