You know that saying, “The eyes are the windows to the soul”? It turns out they might also be the windows to your brain’s future.

Scientists have uncovered a subtle but fascinating connection between how well you see certain shapes—and whether you’re likely to develop dementia over a decade later. Yes, really: your eyes might give away secrets about your brain’s health twelve years in advance.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s the result of a long-term study with thousands of participants, and the findings might just shift how we think about early dementia detection.

A Peek Into the Future Through a Triangle and Some Dots

The study, conducted in Norfolk, England, tracked 8,623 healthy adults over several years. These folks weren’t showing any obvious signs of cognitive decline when the study began. But by the time the researchers wrapped things up, 537 participants had developed dementia.

Here’s where it gets really interesting: at the very start of the study, all participants took a simple visual test. It wasn’t high-tech or invasive. It involved looking at a screen filled with moving dots and pressing a button when a triangle shape appeared.

The results? People who would later go on to develop dementia consistently reacted slower to the triangle than those who remained cognitively healthy.

Not slow enough to raise alarms at the time, but just enough to suggest something subtle was happening under the surface—perhaps years before symptoms like memory loss became noticeable.

Why Vision Might Predict Dementia Before Memory Loss Begins

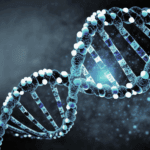

Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, doesn’t attack all parts of the brain equally or all at once. In many cases, the first signs of damage happen in areas related to vision processing. This is often well before the areas responsible for memory start to falter.

One of the main culprits in Alzheimer’s is something called amyloid plaques—sticky protein clumps that disrupt normal brain function. These plaques may begin accumulating in parts of the brain that interpret visual input, like the occipital and parietal lobes, which help us make sense of what we see.

So while you might still remember your spouse’s birthday, you may begin to struggle with detecting shapes, colors, or motion. In other words, your eyes might still be working fine—but your brain’s interpretation of visual input starts going fuzzy.

Read more: Damaging Things That People With Low Emotional Intelligence Often Say

Tiny Visual Hiccups That Could Be Early Red Flags

Researchers have noticed several subtle but telling visual issues that appear early in Alzheimer’s:

- Trouble seeing contrast: Everyday objects might blend into the background.

- Blue-green confusion: This color spectrum tends to get harder to distinguish in the early stages.

- Easily distracted by visual clutter: People may have a hard time ignoring irrelevant details, like blinking lights or background movement.

That last point touches on what scientists call a breakdown in “inhibitory control.” Basically, the brain starts struggling to filter out distractions. This can show up in how our eyes move—or don’t move—during daily activities.

Driving, Focus, and Visual Overload

This decline in visual focus may have real-world consequences. Imagine you’re driving, and your attention is unintentionally drawn to a flashing billboard instead of the road ahead. That small moment of distraction, if paired with delayed response time, could lead to an accident.

Researchers at Loughborough University are actively studying how visual attention deficits tied to early dementia could affect driving safety. The concern is real: even before people report memory problems, their driving might become subtly less safe due to this kind of distraction overload.

The Face Test: Why New People Might Look… Forgettable

One particularly curious aspect of dementia involves facial recognition. Not forgetting who someone is, necessarily—but failing to remember a face you just saw.

Healthy brains tend to scan faces in a very specific pattern: first the eyes, then the nose, then the mouth. This process helps us “encode” the face in memory, so we can recognize it later. People do this instinctively, without even thinking about it.

But individuals in early stages of dementia often don’t scan faces this way. Their eye movements become more erratic or limited, which means they don’t properly register the face in the first place.

In fact, some doctors who work with dementia patients say they can pick up on this during casual conversations—when a patient avoids or fails to track facial features during a greeting or chat.

Read more: Simple 30-Second Test Reveals a Person’s True Character—Using Just One Question

Can Moving Your Eyes Actually Boost Memory? Maybe.

There’s another curious thread researchers are tugging at: eye movement doesn’t just reveal cognitive issues—it might also help fix them.

Here’s the theory: by encouraging deliberate eye movements, especially side-to-side motions, we might stimulate certain memory-related brain functions. This is known as bilateral eye movement.

Some studies suggest these movements can improve autobiographical memory—your ability to recall life events, like your first kiss or where you parked yesterday. And weirdly, the effect seems stronger in right-handed people, though researchers still aren’t sure why.

Other daily activities like reading or watching TV might also be beneficial. These tasks naturally involve lots of eye movement—and people who engage in them regularly tend to have better memory performance and lower dementia risk.

But it’s not just about moving your eyes. Education plays a role too. People with more years of schooling tend to have something called “cognitive reserve.” That means their brains can handle more damage before symptoms show up.

So reading might be good not just for what it teaches you, but for how it keeps your brain moving—literally.

So Why Isn’t Eye Movement Testing a Regular Dementia Check?

If all of this is so promising, why aren’t we using eye tests to screen for dementia in clinics yet?

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Most of the tools used in these experiments—like high-resolution eye trackers—are expensive, complex, and require training to use properly. They’re more likely to be found in research labs than in your average clinic.

Until more affordable, easy-to-use versions are developed, vision-based dementia testing will remain largely out of reach for the general public.

Still, the technology is improving, and as awareness grows, we may see a shift toward using the eyes as a non-invasive, early warning system for brain health.

Read more: The One Change That Can Help You Break Bad Habits and Build Better Ones, According to Science

The Bottom Line: Keep an Eye on Your Eyes

Your eyes may not just reflect the soul—they might also whisper secrets about your brain’s future. From subtle delays in recognizing shapes to struggling with facial focus, your visual behavior could offer clues long before you (or your doctor) suspect anything is wrong.

As science continues to explore the surprising relationship between sight and cognition, don’t be surprised if your next memory test involves watching triangles on a screen or tracking how your eyes scan a face.

Until then, the best things you can do for your brain? Keep your eyes moving. Read. Watch. Engage. Observe.

Because even the smallest flicker of motion might help keep your brain a little sharper, a little longer.