In a world where teenagers are usually glued to video games, social media, or figuring out algebra homework, 13-year-old Brenden Sener from London, Ontario, chose an entirely different path: reviving a 2,000-year-old weapon powered by sunlight.

Yes, you read that right. Instead of experimenting with baking soda volcanoes or growing mold on bread, Brenden attempted to reconstruct an ancient Greek “death ray” first imagined by the legendary mathematician and inventor Archimedes. His goal? To test whether this mythical solar weapon could actually work using modern tools—and he just might have done it.

The Ancient Legend That Sparked a Young Mind

To understand Brenden’s unusual project, we have to go way back to around 214 BCE, during the Roman siege of the ancient city of Syracuse. Archimedes, who was not only a brilliant mathematician but also something of a military engineer, was said to have designed a secret weapon to help defend his city: a death ray.

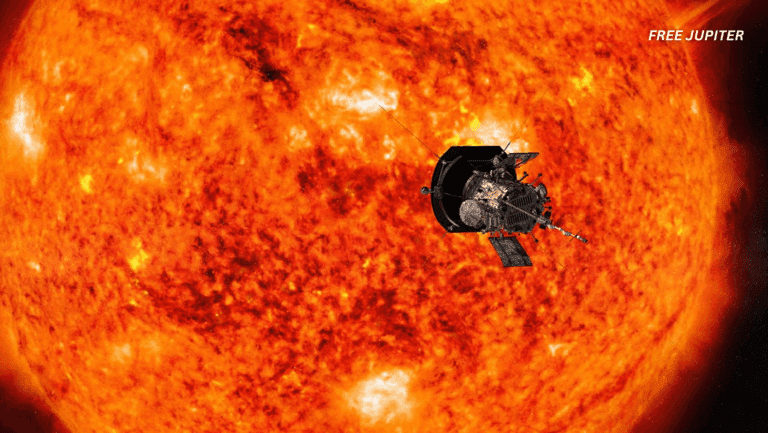

Not the laser-beam kind you’d see in a science fiction movie, but a much simpler concept—an array of large curved mirrors aimed at Roman ships in the harbor. The idea was to reflect and concentrate sunlight onto a single point on the wooden ships, causing them to overheat and, in theory, burst into flames.

While it sounds fantastical, the concept hinges on real physics. Light can be concentrated using mirrors—much like using a magnifying glass to burn paper in the sun. Archimedes’ supposed innovation simply scaled up this effect. However, there’s no physical evidence that this “death ray” was ever actually deployed. No ancient mirrors or defensive installations have ever been found. Just written accounts by historians and philosophers—like Lucian and Galen—who described the dazzling trickery of light during the siege.

A Vacation Turns Into Scientific Curiosity

Brenden’s journey into ancient Greek science started innocently enough. During a family trip to Greece, he was introduced to the works and ideas of Archimedes. At first, he was intrigued by the more practical side of Archimedes’ legacy—particularly the famous Archimedes screw, a device designed to lift water for irrigation or drainage.

But as he dug deeper into Archimedes’ more daring concepts, one myth caught his attention: the solar death ray. Where others saw an entertaining myth or historical exaggeration, Brenden saw a challenge. Could the heat ray, as described in those dusty old texts, actually be possible? And could he recreate a miniature version of it?

That question became the seed of his science fair project—and the beginning of a journey that would eventually win him awards and admiration from real-life scientists.

Read more: Memories Found To Be Stored Throughout The Body, Not Just The Brain, Says Study

Bringing Ancient Optics to Modern Science Class

Brenden began by scaling down the idea to something safe and manageable for a middle school science fair. Instead of lining up dozens of large mirrors under blazing sunlight on the coast, he used a heat lamp to stand in for the Sun and four small concave mirrors to act as the ancient reflectors.

Each mirror was precisely aimed so that the reflected rays would meet at a single point on a target—usually a piece of cardboard. As he added more mirrors, the temperature at the focal point increased significantly.

Through careful experimentation, Brenden was able to demonstrate that the temperature rise was no accident. His controlled setup showed that concentrated reflected light could, indeed, heat up a material enough to suggest the beginnings of combustion. While he didn’t actually set anything on fire, the science was solid.

His conclusion? The principle behind Archimedes’ heat ray was technically possible. That insight earned him a publication in the Canadian Science Fair Journal and multiple medals at the 2023 Matthews Hall Annual Science Fair.

Other Attempts Through History—and on TV

Brenden’s experiment wasn’t the first attempt to validate Archimedes’ claim. The idea has long fascinated historians, scientists, and TV producers alike.

The MythBusters team from the Discovery Channel tested the theory in three different episodes. They arranged large mirror arrays, used the California sun, and even tried to simulate ancient techniques. But each time, they failed to ignite a wooden boat, leading them to label the myth as “busted.”

Of course, the MythBusters’ setup wasn’t perfect. In reality, moving ships, inconsistent sunlight, wind, and poor aiming would all be major obstacles. Still, their work cast doubt on the practical battlefield application of such a device.

Read more: Adversity In Childhood Has Been Linked to Accelerated Brain Development

Meanwhile, a 2005 experiment by students at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) showed more promising results. Using 127 carefully aligned mirrors, they were able to ignite a boat from a distance—once. However, they couldn’t replicate the result under different conditions, making the whole thing feel more like a one-time scientific stunt than a reliable military weapon.

Brenden knew all this. He even referenced these past experiments in his paper. But unlike the MythBusters or MIT students, he wasn’t trying to win a historical debate—he just wanted to know if the basic physics behind the heat ray could hold up under scrutiny.

A Nod from the Scientific Community

Brenden’s effort didn’t go unnoticed. Cliff Ho, a senior scientist from Sandia National Laboratories, who also studied the feasibility of Archimedes’ death ray, commended Brenden’s curiosity and approach. Ho believes that while the physics of the ray is valid, there are just too many real-world limitations—like shifting sunlight, the movement of targets, and the reflectivity of materials—to make the heat ray a dependable weapon.

But he also acknowledged what Brenden’s project proves: that the fundamental science behind the myth is sound.

What Brenden’s Experiment Actually Tells Us

So, did Archimedes really torch Roman ships using mirrors?

We still don’t know. But Brenden’s project adds another brick to the growing wall of evidence that it could have happened. He showed that, under the right conditions, reflected and focused sunlight can create serious heat. And in an age where solar energy is reshaping how we think about power, the experiment is more relevant than ever.

More importantly, Brenden’s work is a perfect example of how science doesn’t always have to be about proving the past—it can be about understanding possibilities. His mini death ray might not have lit any ships on fire, but it certainly lit up imaginations, including his own.

Read more: Scientists Say They Have Discovered Hidden Physics in Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’

Lessons from a Middle School Engineer

While Brenden may not have discovered a new law of physics, his project offers something just as important: the reminder that curiosity is a powerful tool. Whether you’re decoding ancient inventions or imagining new ones, the desire to question, test, and explore is where real learning happens.

His work bridges the gap between legend and reality, science and story, youth and wisdom. And who knows? Maybe one day, Brenden will be designing solar technology that helps humanity in peaceful ways—perhaps using the same principles Archimedes once imagined, but applied with 21st-century insight.

After all, Brenden isn’t just studying ancient science—he’s becoming part of a much bigger conversation about what’s possible when young minds dare to think like the greats who came before them.