Friendly Note: FreeJupiter.com shares general info for curious minds 🌟 Please fact-check all claims—and always check health matters with a professional 💙

There’s something almost otherworldly about seeing fireflies light up a summer night. Their soft, rhythmic blinking seems to pause time, reminding us of barefoot childhood evenings and quiet fields soaked in golden twilight. But in recent decades, these glowing beetles have been slowly disappearing, with many wondering: are fireflies going extinct?

In Illinois, at least, there’s a flicker of hope.

A Childhood Memory That Still Glows

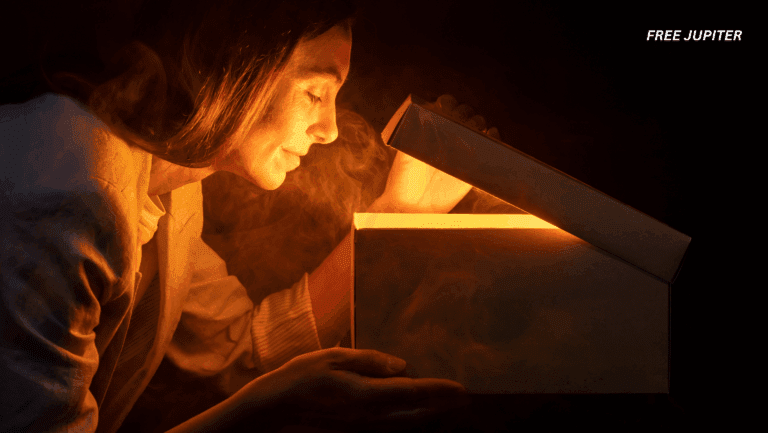

Beatriz Swanson was ten when she first encountered the quiet magic of fireflies in her hometown in Mexico. Two glowing beetles floated before her eyes, and just like that—they were gone. For almost two decades, she didn’t see another. But one dusky evening in upstate New York, that childhood spark was rekindled as a dazzling swarm danced across the sky.

Now living in Plainfield, Illinois, Swanson, 51, recently joined a firefly hike in nearby Bolingbrook. Like a scene from a storybook, she caught two in a jar—watched them blink gently, then set them free. “It’s hard not to feel like a kid again when you see them,” she said with a grin. “There’s just something so pure about their light.”

A Tiny Beetle With a Big Story

Fireflies, technically beetles from the Lampyridae family, aren’t just pretty light shows. They’re part of a delicate ecological web—and a surprising number of them are in trouble.

According to the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, over 2,000 firefly species exist worldwide, with at least 179 species in the U.S. alone. Yet, researchers say some of these species may be quietly vanishing before we even learn their names.

Why? The usual suspects: habitat loss, light pollution, climate change, pesticides. And while some species are still thriving, many are suffering silently.

Read more: These Traits Are Common in People Who Choose Dogs Over Cats

What the Science Says: Disappearing Glimmers

Unfortunately, there’s no comprehensive census for fireflies. Most of what scientists know comes from public sightings, citizen science efforts, and limited field studies. Richard Joyce, a conservation biologist with the Xerces Society and coordinator of the Firefly Atlas Project, points out that anecdotal reports often drive our understanding. That’s why the data can be patchy.

Joyce explains that species depending on wetlands are especially vulnerable, since these habitats are rapidly being developed or drained. Without damp soil and undisturbed leaf litter, firefly larvae have nowhere to grow.

In Illinois, 26 firefly species have been identified. The cypress firefly (Photuris walldoxeyi) is already listed as vulnerable, and six more are “data deficient” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). That means we have almost no idea how well—or how poorly—they’re doing.

Insects like fireflies often don’t get the research funding or attention larger animals do. “We could be looking at a population collapse and not even know it,” Joyce warns.

Climate: A Hidden Firefly Factor

One of the more surprising influences on firefly populations is the weather—not just this year’s weather, but weather patterns over several years.

Darin McNeil, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Kentucky, led a 2024 study that linked firefly population booms and busts to soil moisture and temperature conditions from previous years. Why? Because fireflies spend most of their lives underground as larvae, sometimes for one to two years. That means what’s happening below ground is just as important as what we see above.

“They like moist, but not soggy soil,” McNeil explains. “Too dry, and they can’t find food. Too wet, and their eggs drown.”

So a drought or flood today might result in fewer fireflies two years from now. McNeil’s research also highlighted that soil composition, humidity, and climate shifts play a key role in where fireflies appear and thrive.

This tracks with similar studies in Japan, where species like the Genji firefly have shown notable declines due to changes in river conditions and climate disruption. In fact, a 2020 review in Global Ecology and Conservation warned that climate change could severely alter firefly habitats globally, even in temperate zones.

Other Threats: Light, Lawn, and Lethal Chemicals

Beyond weather, modern life throws several other curveballs at these flickering beetles:

- Light Pollution: Fireflies flash to find mates. But excessive outdoor lighting can interrupt this delicate dance. Streetlamps, porch lights, and even car headlights can confuse fireflies or drown out their signals, causing missed connections during their short mating season.

- Pesticides and Herbicides: These chemicals often seep into the soil, killing larvae or disrupting their development. Systemic insecticides like neonicotinoids, commonly used in agriculture and even home gardens, can linger in plants and soil, potentially affecting firefly prey as well.

- Loss of Leaf Litter: Firefly larvae grow beneath layers of fallen leaves, feeding on snails and worms. Unfortunately, well-manicured lawns and “clean” yards strip away these crucial layers, making modern yards sterile environments for fireflies.

- Urban Development: Roads, sidewalks, and buildings fragment habitats, especially wetland areas. Even small patches of forest or meadow disappearing can have a ripple effect on regional firefly numbers.

Read more: New Study Reveals What’s Really Making People Gain Weight

Can We Bring the Magic Back?

Yes—and it starts in our backyards.

Simple changes can help fireflies thrive, even in suburban or urban areas. Here’s how:

- Turn off outdoor lights at night, especially during peak firefly season (June–August).

- Avoid chemical pesticides and herbicides, or use them sparingly and naturally.

- Leave leaf piles and natural mulch in parts of your yard to provide habitat.

- Plant native species and allow a section of your yard to go “wild.”

- Join citizen science projects like the Firefly Watch Program run by Mass Audubon in partnership with researchers at Tufts University.

McNeil, who participates in Firefly Watch himself, encourages families to get involved. “Even if you count zero fireflies, that’s still valuable data,” he says. “It helps scientists map changes across time and geography.”

The Firefly Atlas, supported by the Xerces Society and partners like the New Mexico BioPark Society, is also collecting sightings and stories. The more we know, the better we can protect them.

Places That Still Glow

In Illinois, locations like The Morton Arboretum and the Chicago Botanic Garden are becoming firefly havens. Spencer Campbell, Plant Clinic Manager at the arboretum, notes that a mix of warm weather, diverse plant life, and conservation-focused landscaping has resulted in some of the best firefly activity in years.

“They’re not just bugs,” Campbell says. “They create moments of awe. They make people stop and watch. That’s not something most insects do.”

Educational events like firefly hikes across Cook, DuPage, and Will counties are helping kids (and adults) rediscover that connection. Equipped with jars and nets, they chase flickers through meadows, learning why these insects matter—and how to protect them.

The Joy of Wonder

For Swanson, fireflies are more than a fleeting summer spectacle. They’re a reminder of something deep and essential. “You just feel… lighter when you see them,” she says. “There’s magic in it. And I want my grandchildren to feel that, too.”

She pauses. “It’s not just about fireflies. It’s about keeping wonder alive.”

Read more: You’ve Been Told ‘Junk’ DNA Was Useless. Turns Out, It’s Absolutely Vital

🧡 In Summary: Why Fireflies Deserve Our Attention

Fireflies aren’t vanishing everywhere—but they are in trouble in many parts of the world. Their decline is silent, scattered, and solvable. From climate shifts to backyard lights, many of the things affecting fireflies are in our control. By understanding them better, protecting their habitats, and simply paying attention, we can keep the summer skies blinking for generations to come.